The remaking of the British working class: trade unions and black and Asian worker in Britain 1949-1984.

[paper given to the Historical Materialism conference, London, 7 November 2013 – you may notice that it is only half-written, running out of steam in the early 1970s. Apologies for that.]

This paper looks at the relationship between black and Asian workers and the trade movement in the post-war period. Its starts at the point after the second world war when a conscious trade union policy on these issues began to emerge, roughly 1949. At best this policy amounted to ignoring, and at worst abetting discrimination. The end point is when the trade union movement began to accept that black and Asian workers faced discrimination and this could not be dealt in terms of the previous policy. This changed attitude became evident in the period around the establishment of the TUC’s Equal Rights Committee in 1975, and the first TUC Black workers conference in 1984, although I will not be looking at the formation of these bodies in detail, but rather the movements of the rank and file in the trade union movement.

Therefore, the first aim of this paper is to establish a narrative of how black and Asian migrant workers were incorporated into the trade unions.

The second is to ask how such a process can be understood. In line with one of the themes of this conference, I will work within the approach to class of EP Thompson, particularly his rejection of structuralism and emphasis on the working class as the key agency of its own creation. As Thompson said, “Class is defined by [people] as they live their own history, and in the end, this is the only definition.”[1] Taking such an approach allows us to bring to forefront the struggles of black and Asian workers as well as the reactions of white workers.

Even before the start of mass black and Asian immigration to Britain, the scene was set by the British government’s response to labour shortages in the years immediately after 1945. Black and Asian labour from the Commonwealth was ruled out, rather white European labour was sought.

Where they were strong enough the unions responded to this by demanding that such foreign labour only be brought in with their agreement, stipulating that foreign workers would not be used to undercut wages, they would be required to join unions, limited in number and in some cases should be the first to be made redundant if jobs were lost. This mindset persisted in the trade unions in relation to black and Asian immigrants. It was long a wish of the TUC to have immigration linked to the demand for labour and specific jobs, sometimes suggesting it be on a temporary basis.[2]

Thus, as late as 1966 the TUC was suggesting that immigrants should not have the same rights as the established workforce. The responsible TUC committee recorded that “it might be impossible … to regard immigrants as having fully equal rights in employment with other members at least for a probationary period” and they questioned whether “a general declaration [against discrimination] could have any appreciable effect on practice at local level, or even on the form of union agreements, which might be based on the ordinary need to safeguard members’ rights against dilution” although this “might be regarded in some quarters as being racially discriminatory in practice.”[3]

The talk of dilution harks back to women taking on jobs considered to be men’s in wartime, and the trade unions seeking agreement that these jobs would be returned to those men at the wars’ end.

The attitude of large parts of the trade movement to black and Asian workers was much the same. Thus, as the TUC received complaints of discrimination against black and Asian workers, their attitude was to dismiss and ignore them.

There were some self-organised black and Asian groups in Britain that complained to the TUC at this time, although without effect. The point here is how black and Asian people were able to organise as workers and in relation to the trade unions. Local trades councils were one way that community groups could articulate with the labour movement. This was demonstrated in the early 1950s when Liverpool Trades Council had a fruitful relationship with the local Colonial People’s Defence Association.[4] However, when the trades council asked the TUC if the Association could affiliate, the answer was no.[5] As we shall see, such community based organisations were to be an important way of bringing minorities marginalised from the labour movement into it. As it happened, the Liverpool trades council went ahead and co-operated with the Association.[6]

But the TUC was unwilling to work with anti-racist organisations or community based groups. The first post-war anti-racist organisation in Britain, Racial Unity, was hardly an exemplar of community radicalism. It was established by the prime minister’s sister, Mary Attlee, who had spent most of her life as a missionary in Africa. Nonetheless, the TUC general secretary Victor Tewson refused to lend his name to support the body.[7]

However, it was neither the TUC nor local trades councils that were in the driving seat of the development of trades unions in the workplace. The key feature of the British labour movement from the 1950s to the 1970s was the power of the shop floor. Here I will argue, following the analysis that Mark Duffield developed in his study of the Iron Foundries of the West Midlands, that it was shop floor politics that played a large part in structuring the racial division of labour.[8]

This could operate by the outright exclusion of black and Asian workers. In 1954 the Anti-Slavery Society wrote to the TUC outlining the case of a Jamaican cooper that a British company, Barton’s Cooperage, had attempted to employ. The union in the workplace, the National Trade Union of Coopers, were only willing to accept union members. When the black cooper applied for membership of the local union, he was turned down on the grounds that no more coopers were need. Since they had three vacancies that they could not fill, Barton’s were convinced that this was purely racist on the part of the union.[9]

There are many more examples of such exclusionary practice by trade unions, and there is no example before the mid-1960s of the TUC attempting to put pressure on any union to do anything about it.

Indeed, the Trade Union Congress of 1954 received a negative proposal that “the influx of coloured workers to this country is becoming an increasingly acute problem” and demanding an investigation and lobbying of the government. Not wanting this debated, the TUC leadership persuaded the movers to withdraw the motion on the understanding that the General Council would consider the issues.. They did not interrogate these questionable assumptions but met with government ministers suggesting that immigration should be controlled so as maintain full employment.[10]

What is most telling about this resolution is that it came from the Ministry of Labour Staff Association,[11] the union that organised workers in labour exchanges and reflected their members’ view that black and Asian immigrants were unsuited to many of the vacancies that were available. While there is little evidence of the state driving the racialisation of labour, nor did it step in stop it until the hesitant steps of the 1968 Race Relations Act. It was only in 1962 that labour exchanges ended the practice writing the letters NCP on the reverse of vacancy cards showing the employer accepted “no coloured people”. Nonetheless, complicity continued. Well into the 1960s the Ministry of Labour circulated a list where discrimination was considered justified. It included:

- The attitude of the trade unions.

- “the class discriminated against have been employed and found unsuitable”

- “That the work concerned calls for a high degree of skill or specialised knowledge which the employer believes that members of a particular race are unlikely to possess”

- “Belief that a particular job is not suitable for a coloured person, e.g. because it involves special Relations with the public”;and

- “Unusual dress” or “appearance”.

What was unacceptable to the Ministry of labour was that discrimination be motivated “simply by prejudice”,[12] although what might constitute this in the light of the above list is unclear.

Thus, with labour exchange complicity and no leadership form the national trade unions, it was the shop floor that structured race in the workplace. Whereas some, such the coopers above, used their power to keep their trade all white, others used it to create a segregation according to skill.

The best known case of this was on the buses where drivers and conductors were considered more skilled than most garage staff. Such hierarchies of skill were often the result of working class struggle, a skilled worker being one in a key place in the production process, skill be only one component of this. Thus white workers racialised the workforce by taking action to stop black and Asian workers entering into skilled grades. White bus crews in the TGWU took such action in 1955 in West Bromwich and Wolverhampton.[13]

It is important to note that these were unofficial strikes without sanction from the union hierarchy[14] and by the 1960s the TGWU was becoming more assertive about challenging their membership. In 1961 a delegate meeting of busworkers in London voted for a ban on recruiting black and Asian drivers and conductors. By this stage this was contrary to the national union’s policy.[15] TGWU officials forced a further meeting which reversed the decision and adopted a policy against discrimination.[16]

Such moves were too little and too slow for the people discriminated against, as the Bristol bus boycott of 1963 shows. This was the result of the publicly owned Bristol Omnibus Company not employing black and Asian people as bus crew. This policy was supported by the white workforce. This was challenged by a local community group, the West Indian Development Council, who encouraged a black person to apply for job. When they were rejected, they mounted a community boycott, and also won the support of the local trades council and the newly elected leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson. Although the boycott was criticised by the local TGWU, who argued that they had been working behind the scenes to end the colour bar, after two months it won.[17]

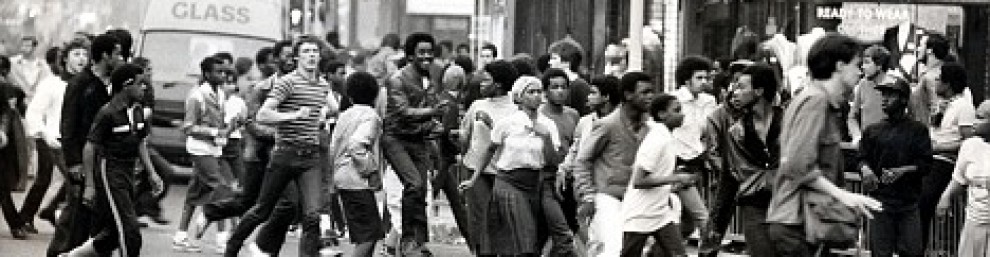

If community pressure outside the trade unions gained results, I will suggest that another key pressure for change was black and Asian self organisation within the trade union movement. There are a number of causes celebres that are frequently cited: the strikes in Woolf’s Southall and Courtaulds in Preston in 1965; Mansfield Hosiery Mills in 1972; Imperial Typewriters in Leicester in 1974 and Grunwick in West London from 1976 to 1978. All are notable for being mainly Asian strikes. They are also the tip of a substantial iceberg of industrial action by Asian workers, the history of which is still to be fully uncovered.

The Woolf’s strike shows some of the dynamics typical of the period. Too much has been made of the importance of ethnic solidarity in relation to the unionisation and strike at Woolf’s. Particularly, attention has been drawn to the role of the Southall Indian Workers Association which in some cases exaggerates its influence.[18] One of important foci of self-organisation is somewhat different. In the late 1950s many recent immigrants, having been supporters of the Communist Party of India in the Punjab, joined the CPGB. The British communists, unsure what to do with members whose grasp of English was often limited, gave them semi-autonomous branches allowing for a degree of self-organisation. It was out of such a CPGB group that the unionisation drive at Woolf’s originated. After many of the Asian workers were signed up to the TGWU, there was a seven week strike in 1966 and 1967 triggered when a worker was suspended.[19] It has been suggested that the strike was hamstrung because the TGWU did not make it official,[20] which is untrue.[21] It has also been suggested that the TGWU was slow to use its members at Fords Dagenham to boycott Woolf’s goods,[22] a fair enough point although whether this differs from the support that the union gave to other workers is a point that might bare further investigation. The strike certainly ended in stalemate in that the workers returned without victimisation although without their demands (particularly pay increases for lower grades) being met, certainly not an inglorious collapse. The strike at Woolf’s did show was the potential for militant shop floor action to push back against the racial division of labour.

Strikes were more complicated when the workforce within a single establishment was divided on racialised skill lines. So more telling was a strike that happened earlier in 1965, at Courtauld’s Red Star Works in Preston. Here:

- Asian workers were concentrated in particular sections within the factory.

- The union involved, the TGWU, negotiated a new agreement on workload and productivity.

- Although the union branch accepted this agreement, the Asian dominated shops were unhappy and went on strike.

The dispute showed Asian workers unrepresented by the mainstream union structures but willing to take their own industrial action outside of these formal structures.

Although the Asians workers were on strike against their employer and against their union, at the end of the five week strike none of the strikers were dismissed and it was reported that working conditions did improve somewhat.[23]

By far the highest concentration of industrial action associated with militant Asian rank and file activists were in the iron foundry industry particularly in the West Midlands. To give a composite picture of these strikes that peaked in the second half of the 1960s:

First. As with Courthauld’s, there was racial division of labour based on grading with Asian workers denied promotion to higher grades.

Second. In the 1950 many Asian workers had joined the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers which failed to promote their interests. By the mid 1960s it was common for Asian workers to decamp to another union en masse, often the TGWU, which they tended to treat as an empty vessel in which they could self-organise at the shop floor level.

Third. When disputes emerged – often over low pay, racially discriminatory redundancies or failure to promote Asian workers – the white unions would invariably not support the strike call and would cross picket lines.

Fourth. Where there were strikes on straight forward trade union issues – such as union recognition – the TGWU was willing to make strikes official. But the TGWU failed to support strikes if the issue was of discrimination.[24]

What had emerged by the end of the 1960s was a powerful shop steward led militant Asian workforce in the Midlands. This led to two cause celebre strikes in 1972 and 1974 which are commonly cited a key factor pushing the TUC to adopt policy recognising discrimination in the workplace.

The first of these was the 1972 strike at Mansfield Hosiery. This strike was essentially about a series of different forms of discrimination that the Asian workers faced at the factory, and won after a 12 week dispute with some support from their union. The Imperial Typewriters strike of 1974 had similar causes, but here the workers won without the support of their union, the TGWU, with the addition threat of the fascist National Front organising against them. Both strikes were notable for being largely Asian strikes against discrimination in mixed workplaces with a division of labour radically structured by race.

To conclude:

These changes in the TU movement should not be over-estimated. There were still clear examples of white only shops of skilled workers in the early 1980s.

Nor should the Grunwick strike of 1976 to 1978 be taken as an indication that all was well in the trade union movement. Although this was a strike largely of Asian workers, the workplace was not structured by race. Nonetheless, it showed the potential of a united working class, present at its own making. Particularly the solidarity shown at the rank and file level with the local postal workers demonstrated that the old hierarchies of skill and race were a little less relevant. That in the end the union leadership of the Union of Postal Workers backed down was a common fate for such solidarity irrespective of race.

There are two ways looking at these changes in union attitudes in the 1970s. Optimistically, one might see the leadership of trade unions pushed by increasingly assertive black and Asian members and their white allies into fighting for both black and white members’ rights.

Negatively, one might suggest that the divisions were becoming a problem for capital, creating intractable disputes amongst the workforce. Certainly, the division of labour at Mansfield Hosiery was not only criticised by low paid Asian workers, but also by an inquiry by the Commission on Industrial Relations, a government body set up to boast productivity.

Ultimately, both are true. The question of who would gain most from a more united working class is only decided by the ability of that class to fight for its interests.

Which brings us to the rather downbeat end of this story. The question of what black and Asian shop floor militancy might be able to do might be able to do if combined with white shop floor militancy was never tested. When Thatcher came to power, small and then large defeats were inflicted on the trade union movement. Shop floor militancy became ossified under the bureaucratic carapace of the new realism in the trade union movement.

Nonetheless, the struggle of the 1960s and 1970s created a trade union movement less divided by race.

[1] EP Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (new Penguin edition, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980 [1963]), p10.

[2] Ref.

[3] Extract from International committee minutes IC 2 dated Dec 20 1966, TUC Archive, Modern Record Centre, University of Warwick, MSS. 292B/805.9/1 (henceforth, TUCA)

[4] Bowling, Benjamin, “The emerge of violent racism as a public issue in Britain, 1945-81” in Panayi, Panikos, Racial Violence in Britain in the Twentieth Century (revised edition) (London: Leicester University Press, 1996, p187. Also see Fryer, Peter, Staying Power(London: Pluto, 1984), pp67-71; The Times Wednesday, Aug 04, 1948/

[5] Letter to R Miller, Liverpool TC from TUC International dept EAB, TUCA, MRC, MSS. 292/805.9/1

[6] Ron Ramdin, The Making of The Black Working Class in Britain (Aldershot: Wildwood, 1987), pp382-387.

[7] Colin Turnbull, Sec of Racial Unity Movement to Tewson, 2/12/1951, TUCA, MSS. 292/805.9/1

[8] Mark Duffield, Black Radicalism and the Politics of De-industrialisation: the Hidden History of Indian Foundry Workers (Aldershot: Avebury, 1988).

[9] Letter from CWW Greenside of the Anti-Slavery Society to Walter Hood, of the TUC Int’l department, 26/07/1954, MSS. 292/805.9/1

[10] Trade Union Congress Report 1955, Trade union organisation and practice, item 75 Immigration form the Commonwealth, p145

[11] Trade Union Congress Report, 1954, p527, agenda item 46 Coloured workers, c.06/09/1954.

[12] The National Archives, LAB 8/3070, “Vacancies involving discrimination”, probably RF Keith, c 30th May 1965.

[13] Ref.

[14] Ref.

[15] “Busmen want colour bar” Daily Mail, 26/6/61.

[16] Employment” in Institute of Race Relations Newsletter, August 1961

[17] Madge Dresser, Black and White on the Buses (Bristol: Broadsides, 1986). Republished by Bookmarks, 2013.

[18] Sasha Josephides, Towards a History of the Indian Workers Association, Research Paper in Ethnic Relations No.18, University of Warwick (Coventry, 1991) [unnumbered, pp31-33 of pdf]

[19] ‘Pakistanis And Indians Clash’, The Times, 06/1/1966. Other contemporary reports are less clear, ‘Lengthy strike talks ease racial fears’, The Guardian, 10/01/1966; ‘Immigrant solidarity shown in strike by Indian workers’, The Guardian;21/12/1965.

[20] John Wrench, John and Satnam Virdee, Organising the Unorganised: ‘Race’, Poor Work and Trade Unions (Research Paper in Ethnic Relations no. 21), (Coventry: CRER, 1995), pp19-20.

[21] ‘Men will lose rights to pension’, The Guardian (1959-2003); 3/01/1966; ‘Immigrant solidarity shown in strike by Indian workers’, The Guardian, 21/12/1965.

[22] Tony Cliff and Colin Barker, Incomes policy, legislation and shop stewards (London, 1966), chapter 7.

[23] Ian Birchall, ‘Ray Challinor and the 1965 Courtauld Strike”, LSHG Newsletter 42 (Summer 2011).

[24] Duffield, pp72-87.

Pingback: The remaking of the British working class: trade unions and black and Asian workers in Britain 1949-1984. | weneedtotalkaboutdominic

Pingback: The remaking of the British working class: trade unions and black and Asian workers in Britain 1949-1984. | British Contemporary History

Pingback: A new British History blog | Hatful of History

Read The Anti-racism Myth: A Flight into the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Chapter I – NATFHE Scurrying Along Towards a Self-imposed Disaster – 1960s to 1984

This covers an overview of racism and sexism in the workplace in the 1960s and 1970s and how trade unions, local authorities and the courts set about dealing with harassment and discrimination. NATFHE’s approach to racism after its formation in 1976 up until its mishandling of the racism issue at Hendon Police Training school in the 1980s is examined.

Free download at http://gordonweaver4.wixsite.com/LegalFerret