A review of Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, Revolt on the Right: Explaining the Support for the Radical Right in Britain (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014)

[If you find the tables difficult to read in this version, click here for this review as a PDF Ford, Robert and Goodwin, Matthew (2014) Revolt on the Right (Review) without notes]

In this new book Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin of Nottingham University offer a rigorous analysis of the electoral support for parties of the radical right in British (or perhaps more accurately English) politics. The space beyond the Conservative pale is now primarily occupied by UKIP, but the analysis necessarily included BNP too, whose electoral fortunes have gone into deep decline since Matthew Goodwin published his 2011 book on the BNP, New British Fascism. Since 2010 UKIP have achieved a degree of success much greater than the BNP had after its breakthrough in the 2003 local elections. Most notably since 2010 UKIP have won second place in four Westminster by-elections, but only in the far from typical Eastleigh by-election came anywhere close to winning.

Whether UKIP can turn that into success in elections to the House of Commons is another matter. Ford and Goodwin examine carefully the seats where the voters are likely to be most attracted to UKIP polices with the incumbents already vulnerable to small swings allowing UKIP to come through the middle between the two main parties. This might allow UKIP to unseat the Conservatives in Waveney or Great Yarmouth (both in East Anglia), both Conservative gains in 2010 but also Labour gains in 1997. To unseat a sitting Labour MP it would require UKIP to attract voters from Labour in a way that they have not done in any of the by-elections held in Labour seats since 2010.

Currently it is the Conservatives who appear worried about UKIP with David Cameron clearly unsure how to deal with them, having backed away from his 2006 tactic of branding them ‘fruitcakes and closet racists’ but seemingly having no better tactic than ignoring them and hoping that the problem will go away. The Liberal Democrats perhaps have most to lose, their position as the default ‘none of the above’ vote having been lost to UKIP and having seen their vote collapse in a series of by-elections since 2010. Nick Clegg misjudged his 2014 debates with UKIP’s leader Nigel Farage believing that debunking Eurosceptic myths would see him home. As Ford and Goodwin show, UKIP’s appeal is one of anti-politics, and so long as Farage appeared more of an outsider than Deputy Prime Minister (hardly a tough call) he could only win.

Labour’s position is to stand back and look at the carnage. Ford and Goodwin suggest that this is short sighted since UKIP’s electoral base is not Conservatives in exile, as believed by those at The Spectator who would like to see the Conservatives take a sharp right turn in social policy to match their economic austerity. Rather they believe that UKIP draws from Labour’s traditional working class base. They argue that:

UKIP’s revolt is a working class phenomenon. Its support is concentrated among older, blue-collar workers, with little education and few skills: a group who have been ‘left behind’ by the economic and social transformation of Britain in recent decades, and pushed to the margin as the main parties have converged on the centre ground. UKIP is not a second home for disgruntled Tories in the shires: they are the first home for angry and disaffected working-class Britons of all political backgrounds, who have lost faith in a political system that ceased to represent them long ago.

While they are careful not to argue that will mean Labour will suffer most, I think this conclusion that UKIP is the product of distinctively working-class anger is questionable as it takes the view that UKIP’s impact could affect Labour as much as the Conservatives. There is very little evidence that the current or past Labour allegiances are the voters that UKIP attract, rather they remain a phenomenon on the right of British politics. Nor are UKIP voters overwhelmingly working class. There is an important debate about what the rise of UKIP shows about the nature and consciousness of the working class (or probably, more accurately, factions within the working class). But Ford and Goodwin push this conclusion too far. They reject the idea that UKIP is fundamentally a rearrangement of the forces on the right of British politics, but that is ultimately what they represent.

One area where Ford and Goodwin’s conclusion are both accurate and important is in pointing out that UKIP are different to the overtly fascist BNP. Everyone knows that every fascist leader has both a suit and a uniform in their wardrobe, and even when wearing the suit (as the BNP increasingly chose to don under Nick Griffin), the fascist concept of taking power is about both the political and physical defeat of their opponents. This is not the case with UKIP, they only have suits. Even when demonstrating his finesse at holding both pint and fag in one hand, Farage remains in jacket and tie. This is something that is lost on sections of the British left. Unite Against Fascism (successor to the Anti-Nazi League, run as a front by what remains of the SWP) have clearly taken the position that UKIP should be treated in the same way as the BNP, which they believe is pointing out how right wing they were and telling the public to vote for someone else, anyone else.

Brighton and Hove Unite Against Fascism, for example, have attempted to disrupt UKIP meetings in June 2013 and February 2014. What is notable watching the YouTube footage of these (posted, note, by outraged Ukippers) is that while it would be foolhardy to disrupt a BNP meeting without having considerable force of numbers, with UKIP there is little sense of personal danger in such an exercise. UKIP are not fascists, they do not seek to mobilise physical force as part of their strategy for gaining power, they exist within Parliamentary democracy which they may damage in some ways but do not seek to fundamentally subvert it (indeed, in their own minds, they believe that are strengthening it). This point is entirely lost on UAF who have produced a leaflet explaining to voters why they should not support UKIP in the May 2014 European Elections. It tells voters ‘Don’t be used by UKIP’, as if the party had a hidden agenda to be sprung on their supporters. It goes on to inform potential UKIP voters that UKIP want a flat rate of income tax, greater military spending, is against gay marriage, that UKIP blames immigrants for economic problems created by ‘the bankers and their rich City friends’, and is racist, sexist and homophobic. Even if pointing out what fascism is and what this means is a strategy for dealing with the BNP in its wearing a suit mode (which it is not), this is doubly untrue with UKIP where there is no deeper design beneath the facade.

Politically, this is a response to the BNP with its strong affinity with the popular front policies of the Communist Parties in the face of fascism after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. This was based on the idea that fascism was particularly bad and it was possible to form a de facto alliance against it with any mainstream democratic party. That it is the wrong policy to deal with the BNP is not the issue here, but it simply does not make sense with UKIP. As Nick Lowles of the anti-fascist organisation Hope Not Hate has pointed out, UKIP is not a far right party and cannot be politically responded to as such. Ford and Goodwin’s book is important in that it starts from an analysis of what UKIP is and where its support lies. The book itself is not a manual on how to oppose UKIP, but it does offer a basis for at least thinking about that in a way UAF seem unable to.

Ford and Goodwin’s book explains that unlike the BNP’s neo-Nazi racial nationalism, UKIP blend more common-or-garden anti-immigrant racism, civic nationalism with social conservatism together with a fair dose of neo-liberal economic policy. In this they have much in common with the right wing of the Conservative Party. Ford and Goodwin go no further than explaining that the roots of UKIP lie in the formation of the Anti-Federalist League (AFL) in 1991 by one-time Liberal and LSE historian Alan Sked. The purpose of the AFL was to stand candidates in for the forthcoming 1992 general election to oppose the federalism of the Maastricht treaty.

Somewhat surprisingly, Ford and Goodwin don’t delve further back in the roots of the AFL. If they had, the origins of the party within the mainstream right of British politics would be more obvious. Perhaps this is reasonable, this is an analysis of UKIP as a force now, not a history of Euroscepticism in the UK. But there is more to say. Sked, even when a Liberal, had been a right-wing Liberal. My memories of reading his (and Chris Cook’s) Post-war Britain: a political history was of it being skewed to issues on the nationalist right, not just Europe but also the Rhodesian crisis and immigration which left a Powellite taste in one’s mouth. The origins of the AFL are not in Liberalism, but Conservatism. When the Bruges Group was formed in response to Thatcher’s anti-federalist speech of 1988, Sked joined. Although the Bruges Group always attempted to present itself as a broad church it was overwhelmingly Conservative, although Sked was unencumbered by the loyalty to the Conservative Party that many of its members felt.

Differences within the group began to emerge between those like Sked whose opposition to federalism was fundamentally on the grounds of political sovereignty, and those with a neo-liberal free market agenda. Sked was not a bystander in these differences. One of the key moments in the differences hardening was the publication in 1991 of a Bruges Group pamphlet by Sked and the group’s founder Patrick Robertson. The pamphlet argued against John Major’s government position on Iraqi Kurdistan in the first Gulf War not so much for the content of policy, but for allowing it to develop as an EU foreign policy. This was a position of overt opposition to the Conservative government that, at that time at least, was problematic for the Conservatives who constituted the bulk of the Bruges Group’s membership. Robertson left in November 1991 and would later resurface as the director of the Referendum Party and later still orchestrated the defence against General Pinochet’s extradition from Britain. Sked lasted a little longer, but when he set up the AFL it was with an intention to run candidates in the 1992 election, at least in Sked’s own account, the Bruges Group kicked him out for potentially disrupting the Conservatives’ re-election.

Nonetheless, Ford and Goodwin do not ignore the complex and changing relationship to UKIP with the Conservative Party. From its start, some in UKIP believed that the party could develop as a broad based electorally successful party, ultimately breaking into Westminster, emerging most notably as the group around the current leader, Nigel Farage. There has been a tension with others who see the party as more likely to succeed in its central aim of Britain leaving the EU by pressuring the Conservative Party. Thus, their leader at the time of the 2010 election, Lord Pearson, was willing to give Conservative Eurosceptics in marginal seats a clear run without UKIP opposition.

Ford and Goodwin’s point is that the Farage party-in-its-own-right tendency has become dominant, forcing the party to broaden its appeal beyond the single issue of leaving the EU to a wider slate of policies. Thus, they see UKIP ceasing to be a parochial oddity, a shadow of the anti-European British Conservative politics, and part of a broader rise in the radical popularist right in Europe. Ford and Goodwin assert this particularly strongly in their analysis of the overlapping, but they argue in some ways for distinct, electoral bases of the BNP and UKIP. This they suggest, places both parties in the context of the European radical right. There is little analysis in this book of the European radical right. If there was it might make the position of drawing a clear distinction between UKIP and the BNP more complex. In a number of European countries the main radical right party is either overtly fascist or clearly fascist in origins (the Front National in France being the main example) or somewhat shady hybrids. Other European countries have both fascist and non-fascist parties on the radical right.

Certainly, UKIP remain unusual in European politics in fundamentally defining themselves by being against the EU. The bloc they align to in the European Parliament is the Europe of Freedom and Democracy group, of which they are the biggest member. Like many groups in the European Parliament, this is a very loose group that exists mainly for the extra resources which being in a group brings its members. The only other large party in the group is the Italian Northern League, which is at best an atypical member of the European radical right. While fitting the mould with strongly anti-immigration (and especially anti-Muslim) policies and a good dose of social conservatism, it has not been consistently anti-EU and its main policies are for greater federalism within Italy. The next biggest party in the bloc is United Poland, a more traditionally right wing Catholic Nationalist Party. Smaller members include the Danish People’s Party which is stridently anti-immigration and anti-multiculturalist and is against Denmark joining the Euro although it is not an anti-European party in the way that UKIP is. With its blend of anti-immigration, nationalism and social conservatism with some pro-welfare policies it is more typical of the popularist right.

Other more clearly right wing popularist parties are outside of this bloc. The Austrian Freedom Party was refused membership, partly at UKIP’s insistence, on the grounds that it was too right wing. The Freedom Party is not dissimilar to the more free-market radical right parties, but it is a party of a political current compromised by Nazism before 1945, something aggravated by an ambivalent attitude towards this Nazi association by some of its leaders. UKIP were alert to the PR disaster that any association with such parties would cause. So the Freedom Party, along with more genuinely fascist groups like the BNP and Front National of France, find their home in the Non-Incripts (non-attached) bloc.

Ford and Goodwin note in passing that compared to many other parts of Western Europe, the radical right was late to arrive in Britain, but do not explain why this happened. Again, a developed analysis here might emphasise how right wing and somewhat popularist Conservative governments under Thatcher from 1979 filled some of this space, and particular after 1987 the defining policy of this current was Euroscepticism. This may be part of the explanation for why the radical right in Britain has emerged in its peculiarly Eurosceptic form, although English nationalism’s lack of any trans-European element is clearly also important.

Even as the space on the right of the Conservative Party opened up after John Major became PM in 1990, it was filled by the insurgency against him within the Conservative Party (and the Referendum Party was only ever an external faction of that Conservative right). That insurgency was victorious in its leadership between William Hague in 1997, IDS in 2001 and ended with the ghost of governments past in the form of Michael Howard to 2005. Only in David Cameron’s period in opposition from the end of 2005 to the 2010 election did the Conservative Party have a more centrist face. If this centrism has declined since the 2010 election, it has done so in a way that has allowed room for the radical right, the government has maintained support for at least some symbolic socially liberal policies, particularly gay marriage.

The Electoral Support for the radical right in Britain.

What lies at the heat of Ford and Goodwin’s book is a fascinating and well argued analysis of the electoral support of the radical right in Britain. They point out that it is possible to see UKIP’s success in entirely conjunctural terms. The election of David Cameron as Conservative leader in 2005 created a space to the right of the party, the collapse in Labour support under Gordon Brown meant that many of the less partisan voters who voted for Blair’s New Labour were looking for another party to vote for; the Eurozone crisis of 2009 discredited the view that European integration was an inevitable one way street; the same year the parliamentary expenses scandal spread more manure on the fertile ground for a growing anti-politics movement. Most of all the entry of the Liberal Democrats into the coalition government of 2010 meant that they were no longer the main repository of protest votes. Ford and Goodwin argue that important as these are, the success of UKIP is not the result of such short term changes but longer term structural changes in class and political representation. They see the move to the centre ground by the two main parties leaving a group of voters ‘left behind’ particularly in terms of English identity and immigration. These are not the ‘Tories in exile’ beloved by The Spectator, but, Ford and Goodwin argue, a section of the manual working class. Thus, although the Referendum Party’s limited success in 1997 may have been based on Southern disaffected Conservatives, Ford and Goodwin argue that the base of both UKIP’s and the BNP’s growth from 2001 are different and particularly after 2004 based on an anti-politics.

This happened for UKIP and the BNP in different ways in different places. The BNP favoured local politics, linking their racial themes to local experiences in area of working class suburban London and Essex and some areas in the North. The BNP’s breakthrough was in local elections particularly from 2003 to 2006 with some slight decline in the period to the 2010 general election, mitigated somewhat by taking two seats in the 2009 European elections in the North West England region and the Yorkshire and Humberside region.

UKIP’s breakthrough in the 2004 was not a result of local campaigning but through gaining a national profile with their brief relationship with the recently sacked daytime TV host (and ex-Labour MP) Robert Kilroy-Silk, and enough funding from ex-Conservative donor Paul Sykes to run a national campaign in the European Parliamentary elections. The result was 16% of the national vote and twelve seats with particular strength in the Midlands and south-east. This result was repeated in 2009, although UKIP failed to make progress in local or national elections within the UK.

Electorally, UKIP’s fortunes have improved since the 2010 election. Ford and Goodwin suggest that Farage’s return to the leadership has seen the party learning from the lessons of the Lib Dems and BNP in building up local support through campaigning in local elections making significant gains in 2013. UKIP’s biggest success, however, has been in by-elections. Ford and Goodwin chart the first fourteen by-elections after 2010, with UKIP repeatedly winning record shares, peaking at 28% in Eastleigh in February 2013, and notching up five second places.

Despite, as Ford and Godwin emphasise, a strong working class element in UKIP’s vote, what they give less emphasis to is that this has not on the whole eaten into Labour’s vote. This is something clearly demonstrated with the by-election since 2010. Ignoring the one Scottish seat (where UKIP are hardly a factor) and Respect’s win in Bradford West these seats were mainly Labour holds which in most cases had swings to Labour greater than to UKIP. The exceptions to this were Rotherham in November 2012, the seat left vacated by Denis MacShane after his resignation because of an expenses fraud, for which he was convicted but not until after the by-election; and in South Shields in May 2013 created by the departure of David Miliband. Here the moves in vote were, in Rotherham ,+1.9 percentage points to Labour, +15.2 to UKIP, and in South Shields, a -1.5 move away from Labour and a 24.2% of the vote for UKIP who had not stood in 2010. Apart from these two examples, there is no evidence of Labour being damaged by UKIP, indeed there is an indication that they may be helped by UKIP taking votes from both the Lib Dems and Conservative while not being able to win themselves. Although the circulation of votes between parties cannot be seen from the raw figures, the net change in votes does not suggest a move of voters from Labour to UKIP.

The table below contains the by-election results since 2010 excluding Inverclyde (UKIP not a factor in Scotland), Bradford (won by Respect therefore far from typical) and Eastleigh (held by the Lib Dems after Chris Huhne’s conviction) all of which have to be considered highly atypical. I have included the one by-election that has been held since Ford and Goodwin wrote their book.

Table 1: Selected Parliamentary by-elections 2010-2014.

The data in this table is limited, particularly since nearly all the by-elections have been in safe Labour seats.

1. It is unfortunate that so few Conservative MPs have died, been convicted of fraud or tired of politics since 2010 since this would have given a more rounded picture of UKIPs impact in Conservative areas. On the evidence of Corby alone, while UKIP clearly did not help the Conservatives, their impact was not great enough alone to explain their defeat by Labour. In the other seats, all Labour holds, if UKIP were making inroads in Labour votes, this is where it would be most noticeable. However, it is not. Rather, UKIP appears on the whole to be taking an excess of Conservative and Liberal Democrat votes in addition to those that (as one would expect) have been won by Labour. It is impossible to say how many of these would go to Labour if UKIP wasn’t there, but there is every reason to believe that in most cases the answer is not many. In most cases, Labour gained healthy swings in their favour.

3. These figures also show, as has been widely recognised, UKIP did not do well in mixed and well integrated urban areas with more relaxed attitudes towards race (Manchester Central, London seats including Croydon). Outside of these areas, in the less integrated, more fractured areas of Barnsley, South Shields etc, UKIP did better. On the whole, both the Conservatives and the Lib Dems have seen a serious decrease in their votes relative to the 2010 election. Labour and UKIP have both benefited from this.

4. Of the constituencies considered here where UKIP had stood in 2010, the mean increase in votes was +6.3 percentage points. This is somewhat skewed by two big swings to UKIP and the median gain in votes was +3.5. Additionally, UKIP gained two strong results in seats where they did not stand in 2010. If these are included, the swings being taken from there give a national average vote of 3.1%, the average gain in votes in all by-elections since 2010 increases to +7.9.

5. The mean swing to Labour (again, taking out the Scottish seats, Bradford and the Liberal Democratic hold at Eastleigh) is somewhat greater as 10 percentage points. Greater than UKIP’s swing and a reasonably good swing for a party in opposition. There is no evidence that UKIP are lessening this swing.

6. UKIP’s gain in votes compares favourably to the swings that the Lib Dems won in the 2005-2010 Parliament in England and Wales, which (ignoring elections with some particular quirk and Lib Dem holds) the mean gain in votes was +3.1. But if by-election results for the 2001-2005 period are examined then the Liberal democrats notched up an average gain of +15.8. In this context it would appear that UKIP are a much less favourable repository of protest votes than the Lib Dems were during 2001-2005.

7. Although in the seven by-elections considered here to November 2012 there was little to suggest that UKIP might damage Labour, there are reasons to believe this is beginning to change. In Rotherham in November 2012 the swing to Labour was low at +1.9 despite the collapse in the Conservative and Lib Dems votes. Even accounting for the impact of Denis MacShane’s resignation over expenses and Respect, who did not stand in 2010, picking up 6.3% of the vote (one has to assume, mainly at Labour’s expense) this shows that UKIP can damage Labour, at least by stopping voters switching to Labour. More ominous for Labour was the decrease in their vote in South Shields by -1.6 percentage points. Despite the collapse of the Conservative vote, and the near total eradication of the Liberal Democrats, the net beneficiaries were UKIP alone. UKIP did not stand in 2010, but looking at the net results, picked up nearly all of the Lib Dem and Conservative lost votes. Labour may have been damaged by an ex-Councillor who ran as an independent and an independent socialist candidate, who between them won 8.4% of the vote. Nonetheless, this does suggest that UKIP are able to block voters returning to Labour form other parties. In the longer term picture in South Shields Labour lost nearly 20 percentage points since their high point in the 1997 election. The Wythenshawe and Sale East by-election (which was held after Ford and Goodwin wrote their book) is perhaps a return to normality, with a sizeable swing to Labour of +11.2, although the swing to UKIP of +14.6 was even greater, fuelled in part by the catastrophic collapse of the previously sizeable Lib Dem vote.

Thus there is some evidence that could be interpreted that since the 2010 election UKIP are increasingly an obstacle to voters returning to Labour but a greater problem for the Conservatives and more especially the Liberal Democrats. But it is as yet unclear whether UKIP will present a problem for Labour at all. Rotherham and South Shields stand out as two results that suggest it may, but all other evidence suggests that UKIP take votes from the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, making serious inroads into the latter’s vote. Ford and Goodwin suggest otherwise, their profile of UKIP voters suggests these are manual workers who might otherwise vote Labour. While the analysis of the profile of UKIP voters is persuasive, some of what Ford and Goodwin take it to imply are the weak points of the book.

Even when Labour were in power, UKIP tended to pick up more votes from the Conservatives. Interestingly, Ford and Goodwin cite figures for this but draw no inference form them. In the period 2005-2007 when Cameron was first leader, they picked up more votes from the Conservatives than Labour. The weakness in Ford and Goodwin’s analysis is that they don’t recognise that there is a faction of the working class who tend to vote Conservative, and since the early 1980s another faction without a strong partisan alignment.

Thus there is little evidence to support the conclusion that:

the older blue-collar white men now backing UKIP are voters who find themselves marginalised in a debate where their voice was once one of the loudest and most respected. This is reflected in their partisan attachments: these groups had strong affiliations, primarily with Labour. In the 2000s a large number ceased to identify with Labour, but found little to like about labour the Conservatives. They dropped out of the political battle, expressing no affiliation to either side and became more receptive to a radical alternative.

The error here is that while the working class as a whole may have strong partisan support for Labour, this is not true of all members. There is no evidence that the working class voters that now support UKIP voted for Labour until the early 2000s, and then stopped voting. There may be factions of the working class who never voted for Labour, or were habitual floating voters, and it may be from these sections that UKIP draw their support. In order to understand this more it is necessary to understand the relationship between the changing class composition of Britain and UKIP’s electoral base.

The Sociology of UKIP voting.

Central to Ford and Goodwin’s analysis is that it is not short term factors that explain the rise in UKIP’s popularity but long term structural changes in the class and political representation in England. In part, at least, they see UKIP’s rise as a response to the way that parties push to the middle ground with UKIP appealing to the resentment of those “left behind”.

Persuasive evidence is presented by Ford and Goodwin to show that there are both similarities and differences between the support that UKIP and the BNP accumulated after 2001. Particularly, the BNP support was on in London (mainly on eastern fringes) and in the north. This is probably less significant now, since the collapse of the BNP into internecine warfare after the 2010, and UKIP have made considerable advances in northern industrial towns. As Ford and Goodwin point out, Farage, in his leadership of the party after 2005, saw the importance of distancing the party from the fascist right. In Farage’s own account to Ford and Goodwin, in 2008 the BNP sent Buster Mottram as an envoy to UKIP’s NEC to propose a pact between the two parties, and Farage used the opportunity to flush out support for such a deal and marginalise it in UKIP. More recently, UKIP have rejected an alliance with the Front National in the European Parliament on the grounds of its anti-Semitism. UKIP have remained sensitive to accusations of racism, Farage and his circle at least being careful to couch their rhetoric in terms of immigration and unassimilated cultural differences with Muslims rather than race per se. While it is possible to see this as a more careful and semi-disguised form of racism, the difference with more overt racialised politics is important and has allowed UKIP to present themselves as part of the political mainstream (although not part of the corrupt political elite).

More importantly, Ford and Goodwin’s analysis suggests that UKIP, like the BNP before them, are succeeding in attracting voters who are less educated males from the manual working class living in areas that are not racially mixed. The appeal to these voters is not fundamentally anti-EU, but an anti-political and anti-immigrant position which Ford and Goodwin suggest is part of a more generalised rise in blue collar support for the radical right across Europe. They suggest that while UKIP’s past electoral base has been one of Conservative splinters, it is becoming much more working class.

This view that UKIP’s success is amongst a section of the manual working class is problematic. This is assumed to be to a section of old Labour’s heartlands, a group who might otherwise have voted not only for Labour but for a more social democratic Labour Party of the pre-Blair days. These voters are seen as those ‘left behind’ by both parties pushing to occupy the centre of British politics. These are voters who would have been integrated into a sense of working class solidarity via the trade union movement and shared communities on council estates before the break up of such working class resources under the Thatcher governments in the 1980s, neo-liberal economic policy and the unmitigated effects of globalised capital. There is clearly some truth in this, the context of the rise of UKIP (and the rise of the radical right in Europe as a whole) is of a change in the working class, its organisational form, ideology and consciousness. But I am far from convinced that it is as straightforward as Ford and Goodwin suggest.

There is no evidence that UKIP’s (or the BNP’s) working class voter were, as a block, ever Labour’s core voters. It has never been the case that the entirety of the working class vote Labour, if they did then Labour would have been in power continuously since 1918. As long ago as Robert McKenzie and Alan Silver’s Angels In Marble (1968), it has been recognised that a sizable faction of the working class vote for parties of the right. There has always been considerable faction of the working class who don’t vote. The history of working class Conservatism may have no relevance to UKIP’s working class voters, but the issue goes entirely unanalysed in this book. Rather, Ford and Goodwin’s assumption that UKIP’s support is drawn from manual workers means that, ultimately, it is drawn from actual or potential Labour voters. The view is that manual workers have been an important source of support for Labour, therefore UKIP have the potential to damage Labour. The missing link that needs to be demonstrated is that UKIP draws support from those manual workers who previously supported Labour. And if Labour’s search for more middle class votes has left those in its traditional heartlands left behind without a party to represent them, then it is entirely unclear that the issues that UKIP voters are identified by (English identity, immigration) have anything to do with the space that Labour has left. Of course, the collapse of class as a form of political identity may have opened this up, but this is not part of Ford and Goodwin’s analysis.

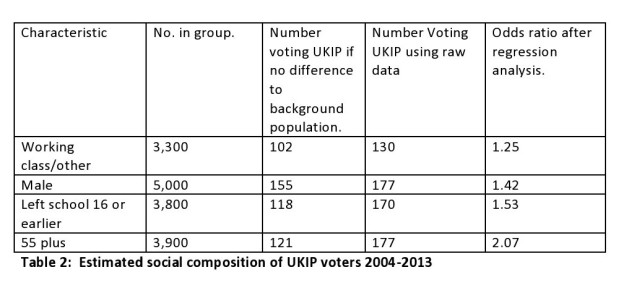

There is a more fundamental problem in the way that Ford and Goodwin interpret their own statistics. Ford and Goodwin suggest that UKIP voters tend to be manual workers, male, over 55 and less educated. The method by which they arrive at this is odds-ratios based on regression analysis (the figures can be found in the table on page 160 of their book). The odds ratio is a useful concept, but one that has to be used with care. The odds ratio for UKIP supporters being working class is 1.25 (although, as far as I can see this also includes the ‘others’ section of the demographic statistics, including those who have never worked etc.). This 1.25 means that a UKIP supporter is 25% more likely to be working class than a voter in general. In other words, if you took 100 votes, 33% of them would be in this ‘working class/other category’; but if you took 100 UKIP voters, then 25% more, around 41%, would be from this category. An odds ratio of 1 would show that there was no difference in UKIP voters and voters as a whole having a given characteristic, and an odds ratio between 1 and 0 that UKIP’s voters would be drawn less from a given group then voters in general.

The relevant odds ratio that Ford and Goodwin arrive at for their profile of UKIP voters are:

• Older than 55: 2.07

• Left school at 16 or earlier: 1.53

• Male 1:42

• Working class (incl. ‘other’): 1.25

[They also include White: 4:09, but that black and Asian Britons do not support UKIP is not of interest here, and I will not analyse this further]

This leads them to conclude that the typical UKIP voter is male, working class, white, less educated and older than 55. This is, however, very misleading. The point is without knowing how many of the general voting population are in each group, the number of each voting UKIP is unclear. Below I have used the figures in the table of raw data of page 152 of their book to reconstruct what UKIP’s voting base is. Consider what this might say of the 3.1% of voters who voted for UKIP in 2010. In the example below I consider a hypothetical group of 10,000 voters. Using the figures from the 2010 election, I’ll assume that 3.11% of these (310) voted for UKIP. Their composition, the figures suggest, would be as follows (I have included the odd-ratio since this is based on a regression that recognises that some of these factors are not independent of each other, the regression analysis adjusting to counter this):

It is clear that UKIP voters are more male, more working class, and less educated than the general population voters. But, less than half are working class. What is notable (and this is even more emphasised after regression analysis) is that they are over 55. Class is a factor in who votes for UKIP, but is the least important factor. It is strange therefore that it is one that Ford and Goodwin concentrate on most. What they should be concentrating on most is age.

Why should age be the single most important factor defining why someone should vote for UKIP? It certainly does not fit with Ford and Goodwin’s ‘left behind’ thesis. It is not simply a question of people getting more right wing as they get older. A much more productive way of thinking about age is through the concept of a cohort, a group of people who have shared experiences through living through the same events at the same time in their lives (although, of course, this varies from individual to individual and may be differentiated by class, education, gender, geographic location etc.). Ford and Goodwin do suggest some slight analysis along these lines, but it is both marginal and not particularly developed. The data that Ford and Goodwin use was gathered across the period 2004 and 2013, so assuming the majority of the cohort to be 55 to 75 at the time of study, this suggests a spread of birth years of around 1930 to 1958. The two points that they make are:

1. This group had direct, or indirect but close, experience of WW2 and thus are less likely to vote for the BNP as the party is seen as neo-Nazi. This seems to me a reasonable point, but one that has little relevance to why they vote UKIP.

2. They grew up at a time when membership of the European Community was more contentious, and thus are more likely to be Eurosceptic. This is much less convincing for a whole range of reasons. Politically, membership of the EU was only opposed by the leadership of the Labour Party for a brief period in the early 1960s. By the 1966 election both Labour and the Conservatives were accepting it. By the time of the 1975 referendum it appeared that membership of the “Common Market” (as it was perceived) was a done deal. Only in the early 1980s did it become contentious again, first in the Labour Party, and then later in the 1980s in the Conservative Party. If these experiences were formative then one would expect the generation coming of age in the 1980s and 1990s, voters aged under 55, to be more Eurosceptic. In fact, the reverse is true. The youngest cohort of voters who have lived through Europe being a constant issue of political debate are the most pro-European. And anyway, as Ford and Goodwin point out, voters are not fundamentally attracted to UKIP on the issue of Europe but on issues of immigration and their English identity.

I would suggest a very different explanation for this skewing in age towards the over 55s. This, I must emphasise, is proffered as a tentative hypothesis and it would take a considerable amount of work to show how sound it is. The voters in the 55+ cohorts came of age in the post-war period, mainly in the period in the 1950s-1970s, the period of British post-war decline. This group mainly lived outside of cosmopolitan metropoles, in northern towns and the provinces. They did not go to university, or even to college. They started work in rather dull jobs in somewhat traditional workplaces and often did not progress beyond those (these were not necessarily manual work, but also retail, financial services, clerical and lower managerial). Mass immigration and the permissive age of the 1960s and 1970s was something of a distant and unsettling spectacle than they saw as part of Britain’s (England’s?) existential decline. The strikes, demonstrations, racial diversity and economic upheavals of the 1970s were something experienced at both a physical and cultural distance. It added to their sense that cultural change in Britain was deeply implicated in economic decline.

In the mid-1970 to the early 1980s this group (along with similar older groups at the time, now deceased) became part of the bedrock support for a more radical, new right, agenda in the Conservative Party and Mrs. Thatcher. If the members of this group hadn’t voted Conservative to this point, they did now. They were the readers of The Sun, Daily Express, and Daily Mail who believed in the myth of the return to Victorian values. With the coming of Major, this group were increasingly cut adrift, and although some may well have voted for Blair’s New Labour vision, the social liberalism of the Labour governments after 1997 alienated them. Particularly after 2005, this social liberalism was reflected by the leadership of Cameron’s Conservative Party, no longer the nasty party but a party comprised of a cosmopolitan elite who are comfortable with gay marriage, mixing with black and Asian on an equal footing and possibly even speaking a European language and eating hummus on a regular basis. To establish this would take some primary qualitative research to complement the quantitative approach taken in Ford and Goodwin’s book.

The irony is that this group is, by its very nature, nearing its sell by date. UKIP voters should soon begin to decline simply because the social attitudes that they represent are not reproduced in new, more cosmopolitan, better educated, citizens. There is an interesting piece of evidence which undermines Ford and Goodwin’s view of a left behind group of working class, previously Labour, voters: the failure of electoral projects to the left of Labour to win significant support. These have proliferated since Tony Blair was elected Labour leader in 1994, and most have attempted to pitch their policies to an old Labour kind of left. The results have been less than startling:

• The Socialist Labour Party (SLP) led by Arthur Scargill ran in 64 seats in the 1997 general election but averaged less than 1,000 votes in each.

• In 2001 they were joined by the Socialist Alliance, including most of the organised left groups outside the Labour Party. The Socialist Alliance contested 98 and the SLP 118 seats, but each candidate averaged little more than 500 votes.

• In 2005 the Socialist Alliance had been superseded by the SWP-George Galloway axis of Respect, although this was already pitching itself much more as a party to attract Muslim votes rather than a more general attempt to occupy a space vacated by Labour. On this basis it won an average of 7 per cent of the vote in the 26 seats where is stood and won a single seat (Geroge Galloway). 49 SLP candidates averaged less than 400 votes each, and the Socialist Alternative (the one-time Militant) contested 17 seats winning a little more than an average of 500 votes in each.

• In 2010 TUSC (including much of what had previously been the Socialist Alternative) stood in 37 seats and won an average of a little over 300 votes each, and the SLP’s decline continued winning a similar vote in the 23 seats it contested.

• In all of these elections a variety of smaller left groups stood, but nothing that alters the overall picture.

None of this suggests a sump of voters left behind by the Labour Party’s shifting to the left. Most telling of all in terms of Ford and Goodwin’s analysis, in the 2009 European Election, the late Bob Crowe led No2EU, an attempt to create a left-wing anti-EU force, and picked up 1.0% of the vote alongside the SLP’s 1.1% (the SLP also has an anti-EU position). None of this suggests that there are left-behinds to the left of Labour that can be easily mobilised even under an anti-EU banner.

And how to deal with UKIP? If, as it appears at the moment, that UKIP is a force that is fundamentally an epiphenomenon of British conservatism, this is a non-question. UKIP is unlikely to gain any form of power beyond winning seats in local councils and the European Parliament. They are unlikely to break through into Westminster politics and differences within UKIP are likely to lead to fracturing along the way. The left should, for sure, counter its racist, anti-immigrant popularism. The trade union movement and the Labour Party (as far as it has any fight left in it) should answer the questions of jobs and housing not with controls and immigration but with new social housing and economic policies based on need not profit.

Thus, UKIP are fundamentally a splinter of the right wing of mainstream Conservatism, both in terms of their ideas and their electoral support. They are not fundamentally ‘angry and disaffected working-class Britons’, it seems more likely that they are a socially marginal group that took Thatcherism seriously. They are not part of the future, they are a shadow of the past. Of course, politics is a fluid business. New wine can be decanted into old bottles, and UKIP may be able to reposition itself to attract young voters (as the BNP did), it might shift to the right and become more like some other radical right European policies, or it may shift left to become more defensive of welfare. But at the moment it appears to be zombie-Thatcherism.

Pingback: UKIP – Suited not Booted | British Contemporary History

Pingback: Second Thoughts on UKIP | British Contemporary History

Pingback: UKIP and the 2015 general election: is the Farage balloon beginning to deflate? | British Contemporary History